Abstract:

In a study published in Nature Communications, cancer researchers at Kanazawa University identify mechanisms by which malignant tumor cells extend their toxicity to distinct cell types and in turn help them spread.

Most tumors consist of a heterogenous mix of cells. Genetic mutations found only in some of these cells are known to aid with the spread and progression of cancer. However, oncologists often find that when tumors metastasize to distant organs, they retain this heterogenous nature—a phenomenon termed “polyclonal metastasis”. The mechanism by which non-metastatic cells accompany the metastatic cells is ambiguous. Now, Masanobu Oshima and his research team have used mouse models to explain how non-metastatic cells begin their long commute.

The team has previously developed various cancerous mutants of mice and analyzed them closely to reveal which cancer cells inherently spread and which do not. It was found that cells with four mutations, colloquially termed AKTP, were the most fatal. When these cells were transplanted into the spleens of mice, they migrated to and formed colonies in the livers within 3 days. In contrast, cells with two mutations, AK and AP, could not traverse this distance. To replicate polyclonal metastasis, AP cells were then co-transplanted with AKTP cells, and voila, both cell types indeed moved into the livers. Instead, when AP cells were injected into the blood (without prior exposure to the AKTP cells) they could not metastasize. Certain processes seemed to be at play when the cells were incubated together.

Next, AKTP cells within the liver tumors were killed to see how closely that affected the AP cells. The AP cells continued thriving and grew into larger tumors suggesting they did not need the AKTP cells anymore. Thus, at some point in the journey from the spleen to the liver the AP cells turned dangerous. To identify this point, the researchers traced back the chain of events. Within a day after transplantation, AKTP clusters were found in the sinusoid vessel, a major blood vessel supplying the liver. By 14 days, this cluster transformed into a mass termed as a “fibrotic niche”. The same mass was observed with a mix of AP and AKTP cells, but not with AP cells alone. What’s more, within this mass AKTP cells were activating hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). HSCs are responsible for scarring of liver tissue. Activated HSCs then set up the perfect environment for AP cells to proliferate infinitely. Harboring the AP cells within the fibrotic environment was, therefore, a key step.

“These results indicate that non-metastatic cells can metastasize via the polyclonal metastasis mechanism using the fibrotic niche induced by malignant cells,” conclude the researchers. Targeting this fibrotic niche might be a promising strategy to keep the spread of solid tumors in check.

[Background]

Polyclonal metastasis: Solid tumors such as breast and colorectal cancer are famous for spreading notoriously. These tumor cells break off from the point of origin and migrate via the bloodstream into distant organs to set up shop. It is often found that such metastatic tumors are genetically diverse in nature. However, the role of cancer mutations in conferring tumors metastatic is still unclear. Older theories have suggested that genetic alterations are the sole key to turning cells metastatic. However, the study depicted here shows that other mechanisms are also at play.

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and the fibrotic niche: HSCs are specialized cells of the liver responsible for scarring and wound healing mechanisms when activated. Upon activation, (after events such as liver damage) HSCs start proliferating and induce fibrotic tissue within the liver. Thus, their activation by AKTP cells resulted in development of the fibrotic niche, an environment particularly favorable for tumor proliferation.

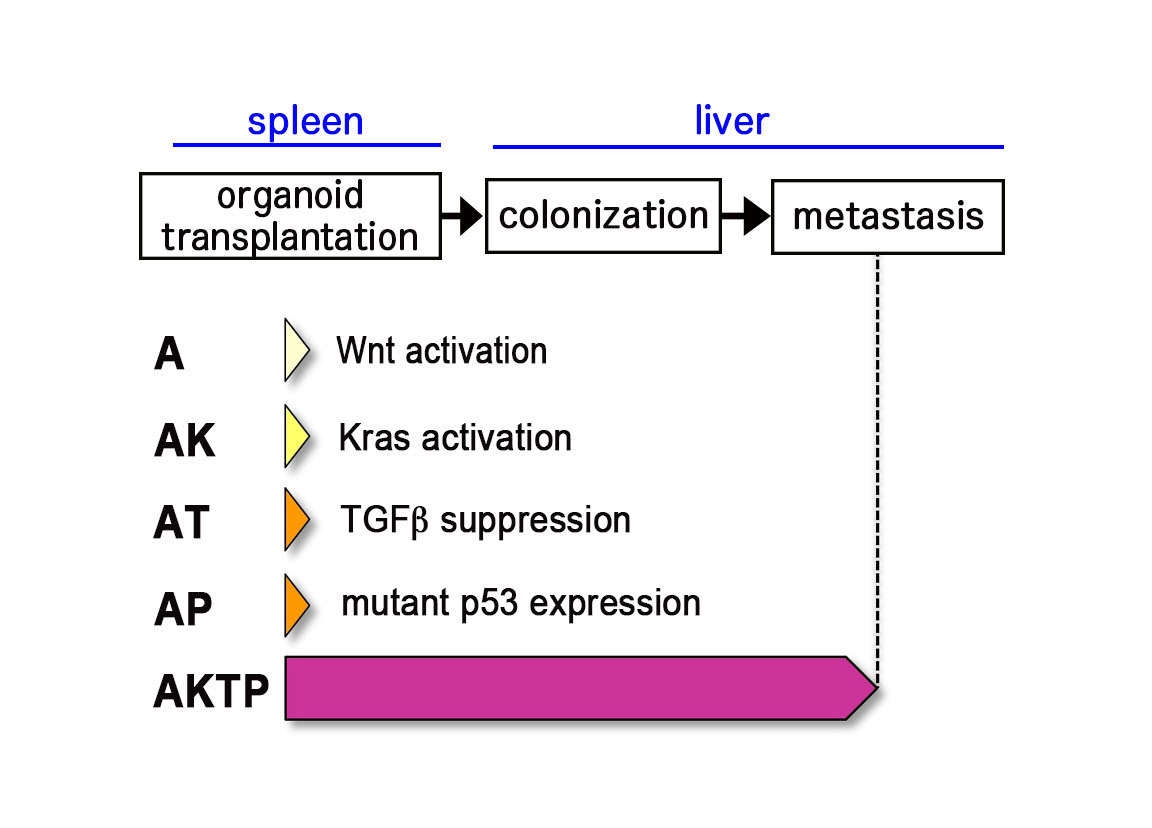

figure1. Mouse intestinal tumor-derived organoid cells.

A~AP are non-metastatic cells, while AKTP cells develop liver metastasis when transplanted to spleen.

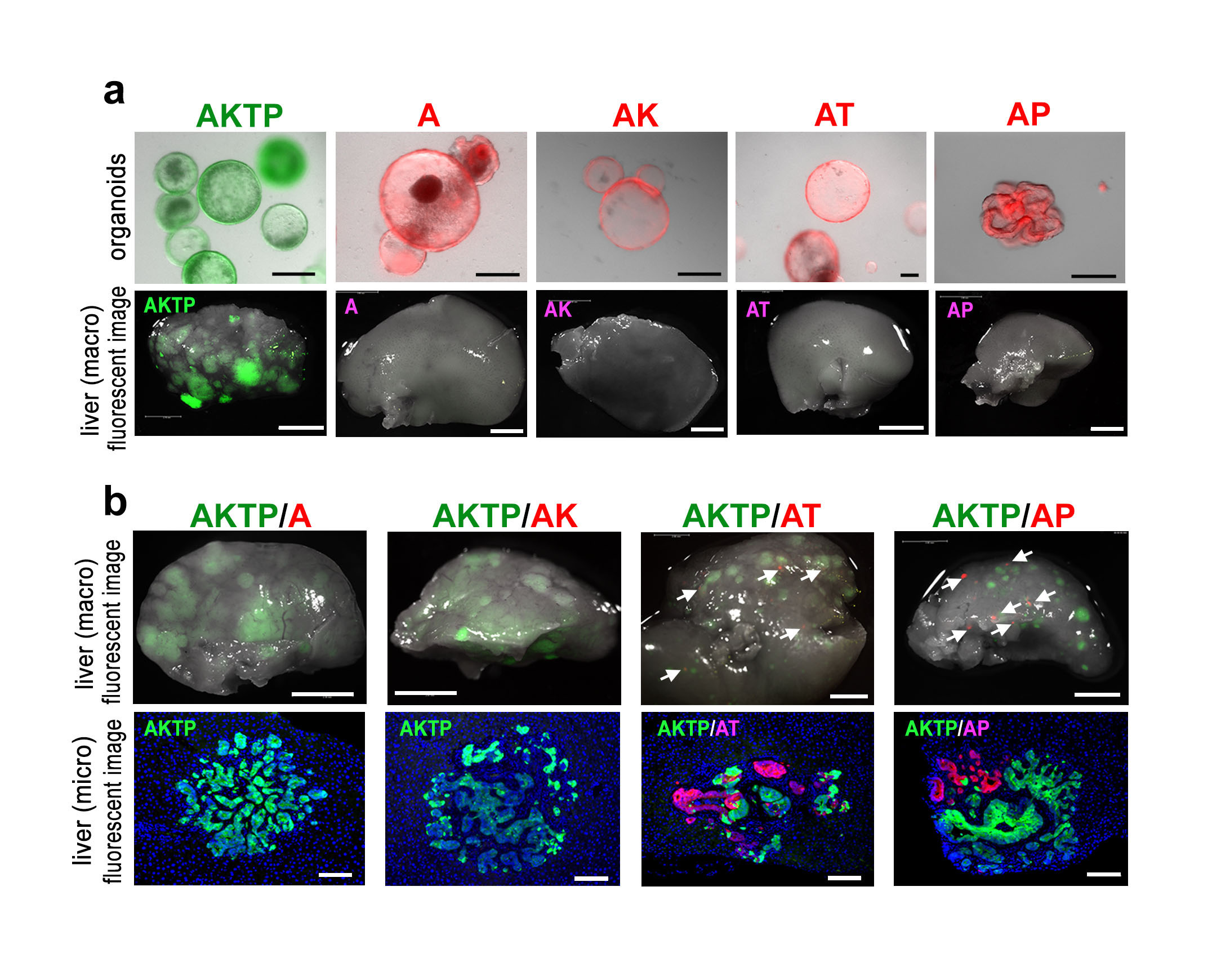

figure2. Organoid transplantation experiments.

(a) Fluorescence-labeled organoids (top), and liver tissues (macro images) of organoid-transplanted mice under fluorescent microscope (bottom).

(b) Liver tissues (macro images) of chimeric organoid-transplanted mice under fluorescent microscope (top), and fluorescent immunohistochemistry of metastatic lesions. Note that AT and AP cells metastasized with AKTP cells as clusters.

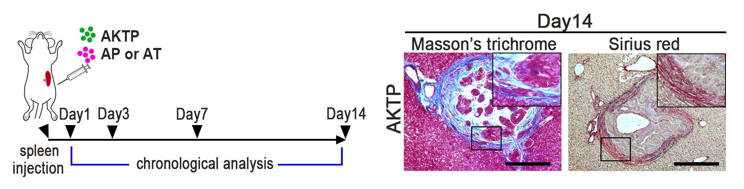

figure3. Transplantation schedule to mice (left), and fibrotic niche generation at metastatic site consisting of AKTP cells in the liver (collagen staining, right).

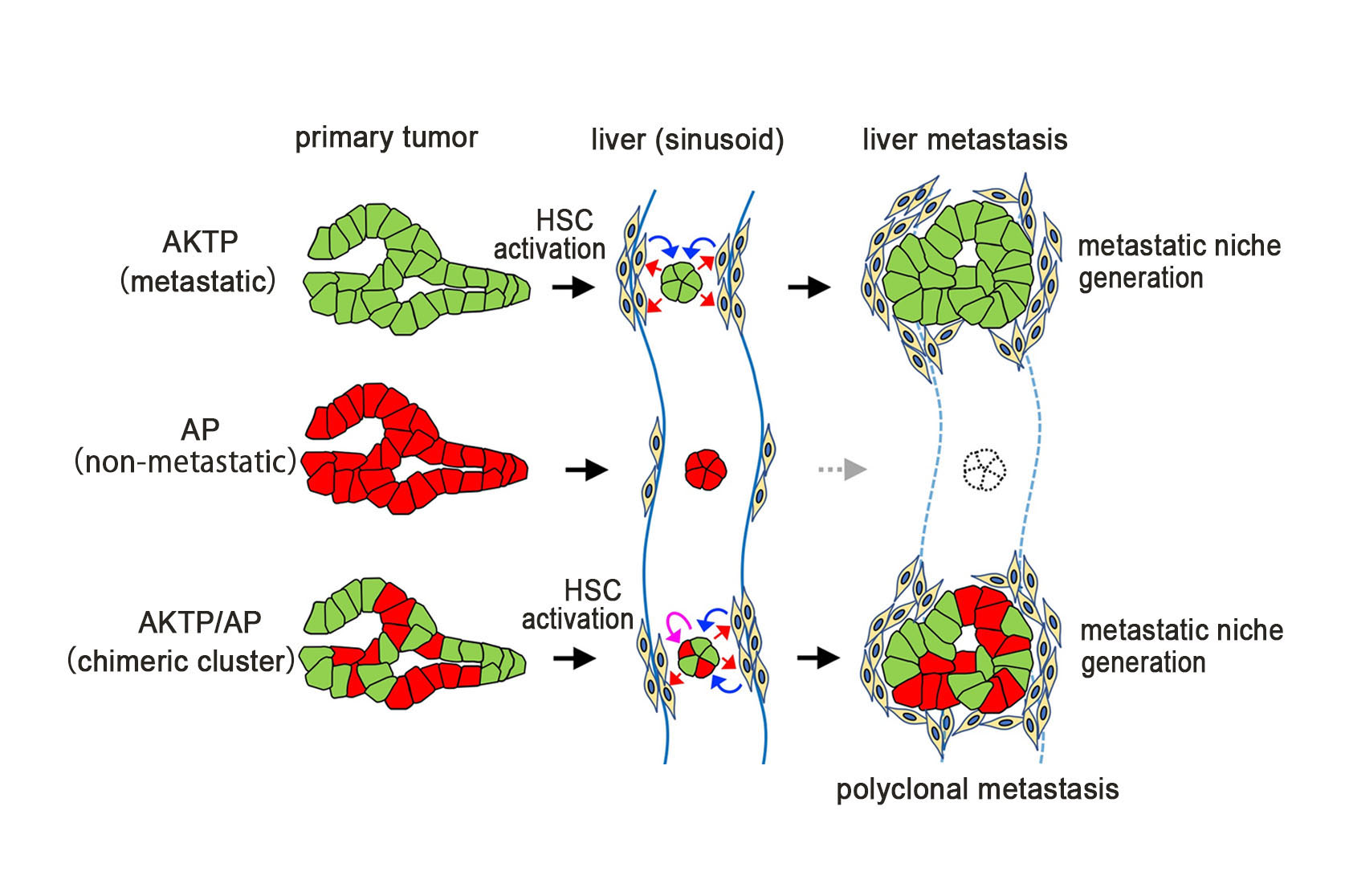

figure4. Schematic drawing of polyclonal metastasis.

Metastatic cells generate metastatic niche by activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Non-metastatic cells can survive and proliferate with the presence of such metastatic niche, resulting in polyclonal metastasis development.

[Article]

Title: Malignant subclone drives metastasis of genetically and phenotypically heterogenous cell clusters through fibrotic niche generation

Journal: Nature Communications

Authors: Sau Yee Kok, Hiroko Oshima, Kei Takahashi, Mizuho Nakayama, Kazuhiro Murakami, Hiroki, R. Ueda, Kohei Miyazono, Masanobu Oshima

DOI: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-21160-0

[Funder]

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, Japan (AMED) (19ck0106259h0003, 20ck0106541h0001), JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (18H04030), (B) (19H03498) and World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan.

PAGE TOP

PAGE TOP